It’s an illegal practice the FTC has challenged for decades: companies convincing consumers to pay for “repairs” on products that don’t really need fixing. The FTC alleges that Office Depot and service vendor Support.com engaged in a 21st century version of that misleading tactic. According to the complaint, the defendants tricked customers into spending millions on repairs by deceptively claiming they had found malware symptoms or infections on consumers’ computers. Separate settlements totaling $35 million convey the clear message that what really needed fixing were the companies’ sales methods.

The story starts when Office Depot brought Support.com on board to do computer repairs in Office Depot and OfficeMax stores. (Both chains are owned by the same company, Office Depot, Inc.) Office Depot branded the services as their own, but Support.com employees performed the services by remotely accessing computers that people brought to Office Depot. The companies divided the proceeds.

As part of the arrangement, since at least 2009 Support.com provided Office Depot with software called PC Health Check. Advertising the PC Health Check Program in its stores, on radio, and in print as a “free PC tune-up” or “free PC check up,” Office Depot promised that a “tech expert” would “run complete diagnostics” to “optimize” the consumer’s computer. Other promotional materials pitched the program this way: “Improve overall system performance. Security Assessment. Scans the system for viruses.”

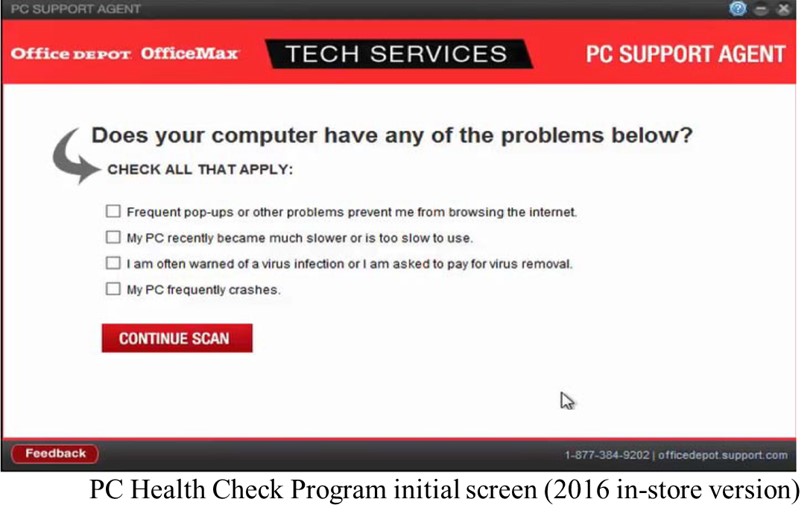

Once the defendants had consumers in the store, employees installed PC Health Check and ran it in the consumer’s presence. The screen initially displayed the question “Does your computer have any of the problems below?” Checkbox options were:

- “Frequent pop-ups or other problems prevent me from browsing the internet.”

- “My PC recently became much slower or is too slow to use.”

- “I am often warned of a virus infection or I am asked to pay for virus removal.”

- “My PC frequently crashes.”

Next came the “scan.” You’ll want to read the complaint for a detailed explanation, but it boils down to this. According to the FTC, the defendants configured the PC Health Check Program to report that the scan had found malware symptoms or infections regardless of whether the computer was infected. The malware symptoms diagnosis was triggered by checking the box next to any of those four fairly generic “symptoms” on the initial screen. Even when the program purported to be running a “Quick Malware Scan,” it was the checkbox – not the scan – that generated the diagnosis of malware symptoms.

Beginning in 2012, complaints about the practice started bubbling up from a particularly credible source: store employees. For example, even before the merger, OfficeMax used the PC Health Check Program, too. An Office Max employee told corporate managers that the software would report malware symptoms on a computer that “doesn’t have anything wrong with it” simply by virtue of the checked box. The employee wrote, “I cannot justify lying to a customer or being TRICKED into lying to them for our store to make a few extra dollars.”

Even as complaints continued to come in from employees and other sources, how did Office Depot respond? It told employees to continue advertising the service, to continue to run the PC Health Check Program, and to convert 50% or more of all runs into tech support service sales. According to the FTC, Office Depot actually paid extra commissions to store managers and employees who met their weekly goals for PC Health Check runs and tech service sales and reproaching those who didn’t.

In late 2016 a Seattle area TV station aired a segment reporting that Office Depot stores were claiming to detect malware on computers that were brand new. That’s when the company finally suspended its use of the PC Health Check Program.

The complaint charges that Office Depot falsely represented that the PC Health Check Program had detected infections or symptoms of malware on consumers’ computers and that Support.com provided Office Depot with the means and instrumentalities for the commission of deceptive practices. In addition to provisions that will change how the companies do business, the proposed settlements require Office Depot to pay $25 million and Support.com to pay $10 million more.

What can other companies take from the case?

Service representations are subject to the FTC Act. Even if you’re careful to substantiate your product claims, what about your service promises? They’re covered by established consumer protection principles, too, and you need appropriate proof to back up those representations.

Fear-mongering shouldn’t be a sales strategy. When a service professional reports that the doohickey is dying or the thingamabob is about blow, a consumer’s understandable response is to reach for the wallet, especially when the warning is about complicated equipment people aren’t in a position to repair for themselves. For many consumers, computer security concerns fall into that category. It’s unwise for companies to exploit those fears falsely for their own economic benefit.

Clarity begins at home. When employees express concern about a questionable business practice, savvy executives pay attention. Heeding in-house early warnings and responding appropriately may be able to prevent a more serious predicament.

Source